In embracing te Tiriti, we see He Ara Waiora as being both complementary to a broader understanding of wellbeing, and a distinct Māori perspective on wellbeing. For example, we see the explicitly holistic and intergenerational approach as complementary to other wellbeing frameworks such as the Living Standards Framework, while recognising the underlying concepts and principles as distinctly Māori. As noted by Treasury, “many of its elements are relevant to lifting the intergenerational wellbeing of all New Zealanders” (The Treasury, 2022, p. 19).

He Ara Waiora is also the source of the five values we propose for how the Government and public management system should act to enhance the mana and wellbeing of individuals, their families, whānau and communities (McMeeking et al., 2019). These values are listed below and described in more detail in Chapter 4 (Box 6).7

- Kotahitanga – working in an aligned, coordinated way.

- Tikanga – making decisions in accordance with the right values and processes including in partnership with te Tiriti partners.

- Whanaungatanga – fostering strong relationships through kinship and/or shared experience that provide a shared sense of wellbeing.

- Manaakitanga – enhancing the mana of others through a process of showing proper care and respect.

- Tiakitanga – guardianship, stewardship (for example, of the environment, particular taonga or other important processes and systems).

Disadvantage has a temporal dimension. Our terms of reference directed us to focus on “persistent disadvantage”, which we have defined as being ongoing or recurrent over two or more years, or over a life course. Intergenerational disadvantage is persistent disadvantage that occurs across generations. The companion report to this report provides more discussion on various forms and definitions of disadvantage, including examining patterns of persistence, recurrence and temporary disadvantage (of less than two years).

Drawing on several studies, our interim report highlighted factors with an intergenerational impact on wellbeing and disadvantage. These factors included maternal education, cultural disconnection, adverse early life experiences, housing quality and the toxic stress that results from a lack of material resources.

Although these factors are symptoms of disadvantage, they also generate further disadvantage through their impacts on childhood development and educational achievement, which flow into adult employment, health and economic outcomes, which then impact the next generation (NZPC, 2022a, pp. 52–54).

The Treasury’s recent wellbeing report highlighted that our current generation of younger New Zealanders fare worse than older people on mental health, educational achievement and housing affordability measures (The Treasury, 2022, p. 2).

In recognising the complexity of the world and the factors that cause and sustain persistent disadvantage, we have taken a systems approach to understand how to address root causes of persistent disadvantage.

Although the causes of disadvantage often lie outside the public management system, policy choices can directly and indirectly affect people’s ability to thrive. The public management system has a powerful influence on determining whose voices are heard and acted on during policy development, what information and evidence is drawn on, what frameworks and tools are used to inform advice and decision making (including funding decisions), what eligibility criteria may be set, and how people in the system are held to account.

Further, public service leaders and the public service as an institution have both a duty of care to “strive to make a difference to the well-being of New Zealand and all its people” (State Service Commission, 2007) and a stewardship obligation.

The focus of this inquiry is on how the public management system can shift to enhance the wellbeing of New Zealanders and better achieve a fair chance for all, especially people experiencing persistent disadvantage.

The relationship between productivity and wellbeing

Productivity and wellbeing are interrelated in a complex way. Wellbeing has multiple influences, with productivity being just one of them. Greater wellbeing can also lead to higher productivity.

For the Commission, the primary purpose of increasing productivity is to lift the wellbeing of New Zealanders. Understanding the relationship between the two allows us to approach our work in a way that makes productivity meaningful and not merely an end in itself. This allows us to focus on what is beneficial for the people of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Our terms of reference called on us to “explore how realising people’s potential (through reducing persistent disadvantage) translates into direct increases in wellbeing, as well as higher productivity and better economic performance”. This is a large area of research and would require substantial time and resources to comprehensively quantify. Although the economic benefits are likely to be large (see Box 1 and the Commission’s supporting paper that draws on available literature (NZPC, 2022b), we consider that the human rights and public good arguments are just as important, if not more so.

|

Box 1 Reducing persistent disadvantage could raise productivity and create substantial social and economic benefits for everyone

|

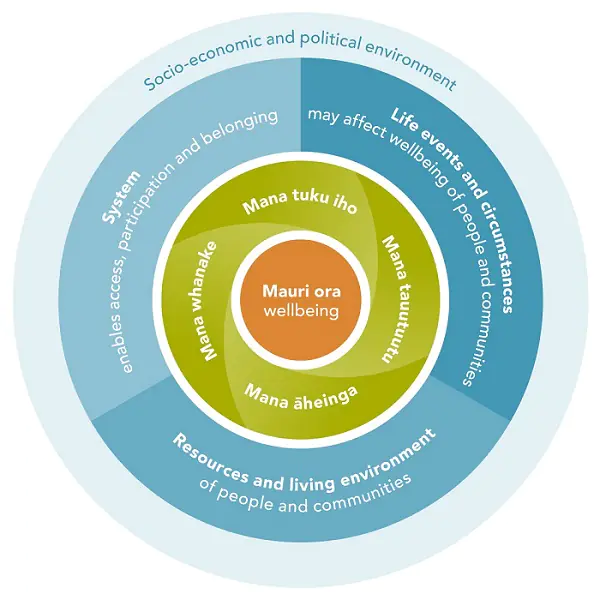

The main social and economic benefits of reducing persistent disadvantage (seen through the lens of our Mauri Ora approach) include:

- enhanced prosperity (mana whanake) through an increase in economic output, productivity and contribution to our communities through paid work and unpaid work;

- greater intergenerational prosperity and system stewardship (mana whanake) through better use of public resources by freeing up government investment to support prevention, instead of dealing with emergencies that arise from people exposed to disadvantage;

- enhanced capabilities and opportunities (mana āheinga) through more resources available to support future social and economic wellbeing, including increased support within communities, investment in skills and knowledge, new technologies, and innovation;

- enhanced identity and belonging (mana tuku iho) through greater social cohesion and trust within communities; and

- enhanced connectedness (mana tautuutuu) through stronger democratic processes by giving more people a voice in decision making (NZPC, 2022c).

Persistent disadvantage wastes the talents and contributions of people who are unable to fully support their family and whānau and fully participate in their communities and the wider economy. These lost opportunities do not just impact individuals who experience persistent disadvantage; they make all New Zealanders worse off, including future generations.

Although we have been unable to directly quantify all of these costs due to data limitations, the total impact of reducing persistent disadvantage is likely to be large. A New Zealand study in 2011 estimated that child poverty alone costs Aotearoa New Zealand $8 billion per year – equivalent to 4.5% of GDP in 2011 (Pearce, 2011). A further breakdown of these estimates reveals that if child poverty was eradicated, around one-third of the benefit goes directly to the individual through higher employment income. However, two-thirds of the economic benefit would accrue to the broader community in the form of increased employment income, lower preventable expenditure by government on welfare, health and justice, and the benefits of avoiding the costs of overcrowded health services and crime in people’s day-to-day lives (Holzer et al., 2008).

|